It’s that time again, I’ll be starting my recurrent, followed by some Rest and Relaxation. No posts for the next few weeks, but I will be back with more obstacle clearance information. See you then.

The Art of Obstacle Clearance on Departure … end of Part One

In yesterday’s post I asked about your most recent flight. Specifically, how did you, without checking your AFM first-segment climb gradient chart, know beyond the shadow of a doubt you were going to cross the departure end of the runway at a minimum of 35 feet.

The answer I was looking for is:

You did this when you determined your takeoff distance on the day, and checked to make sure you had at least that much runway. The number your AFM, QRH or perhaps your FMS gives you, guarantees you – as much as that is possible – that you will, in that distance, be able to either:

- accelerate and reject the takeoff if an engine failure occurs before V1,

- accelerate and continue the takeoff if an engine failure occurs at V1 – AND CROSS THE DEPARTURE END AT 35 feet, or,

- accelerate and continue the takeoff if no engine failure occurs – AND CROSS THE DEPARTURE END AT 35 feet.

In the last case, you’ll actually need less than the stated distance, because that gets “padded” by 15%.

You can read up on that in the FARs here.

Note that’s for a dry runway.

Next, I’ll talk more about the hurdles the departure procedure designers usually put in place to let us know what we have to do to be safe. Look for another post shortly but not immediately – I’m still working on the illustrations I’m gonna need.

Email b l o g @ e 6 b j e t . c o m if you have comments. I read them all, just can’t promise a reply. Please explicitly state if it’s okay for me to use your reply in future posts.

Cheers

The Art of Obstacle Clearance on Departure… continued

My previous post had a 10-second video of a takeoff, and asked what happens right at the end of the video. A bit of a loaded question it was…

Note I will be talking about transport-category aircraft in this series. Those that are certified under FAR Part 25, or EASA CS-25. I’ll use the US regulations, but EASA’s are very similar.

The Answer

Here’s my answer. And another question, further down.

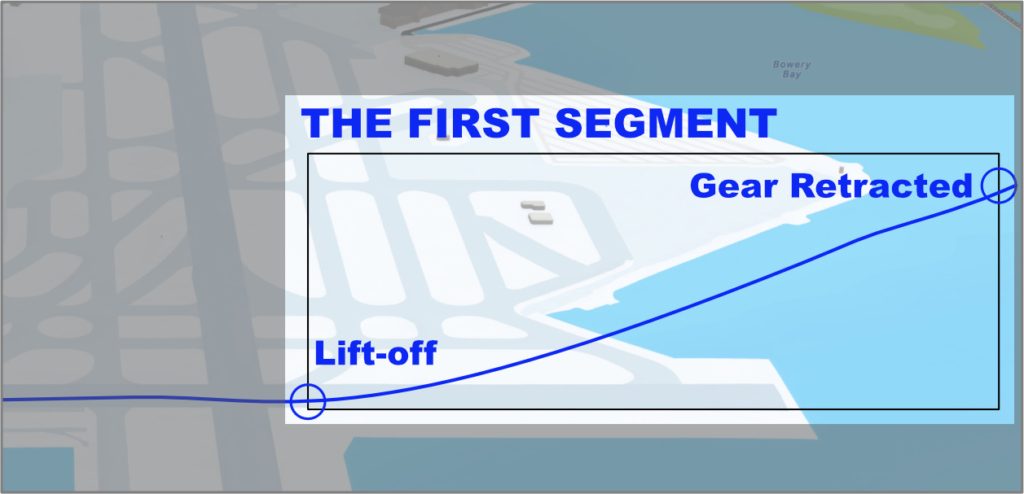

The gear having fully retracted and the doors closed, the aircraft reached the end of what is called the first segment in Aircraft Flight Manuals.

Some details about the first segment. Not hugely important.

Is this information about the first segment important? Well, in the grand scheme of all things Obstacle, not that much. But what is important is that you be able to answer the question down at the bottom of this post. And it might help with that.

You’ll have heard the term. Pilots tend to also remember that the first segment starts at lift-off, and that for two-engine aircraft, the climb gradient must only be positive *. And then try to forget what seems like unclear and worrisome knowledge.

In practical terms, that blue line in the diagram above has to be going up after lift-off and until the wheels are in the well. Though it doesn’t have to go up much.

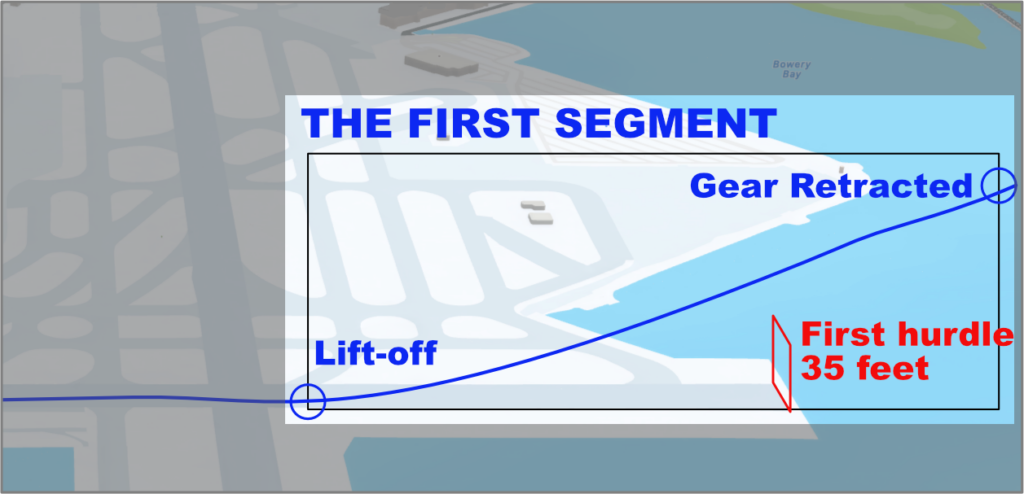

Fictitious example: that twinjet of yours can do a 0.5% first-segment climb gradient. You’re taking off from a 5000-foot runway, lift off at the 2000-foot mark. Well, you’re gonna cross the departure end of the runway at 15 feet.

The folks who certified the airplane were happy with this. Are you? Probably not. There’s a different bunch of folks who design departure procedures for airports, and they have a completely different set of hurdles they want airplanes to overcome when taking off. And we have a vital interest in overcoming these.

The first requirement is usually that you’ve got to cross the departure end of the runway at a minimum of 35 feet. There’s more hurdles, but let’s do one thing at a time. Here’s the diagram again, with the designer’s first hurdle drawn in red.

The next question

So here’s the next question I’ll leave you to mull over for a while.

What did you do, before your most recent takeoff, to ensure that you could indeed make that first hurdle at 35 feet?

Allow me to highly doubt you pulled up your first-segment climb gradient charts, regular pilots don’t regularly do that.

Yet I’m sure you did check. How’d you do it?

My answer tomorrow.

- For three-engined aircraft the requirement is a bit better, the gradient must be a still-paltry 0.3%, and 0.5% if you have four engines. Technically, the first segment really starts when the aircraft reaches VLOF. Read up on it here, § 25.121 specifically.

The Art of Obstacle Clearance on Departure… Part One

Not the easiest topic, but I’ll give it a go. In bite-size chunks. I’ll do several posts on this, this is the first.

First, watch the 12-second video below, it’s a takeoff and initial climb from a chase position.

Then answer one question:

Something happens right at the end. But what?

Don’t watch it more than once or twice, you’re not looking for something tiny, subtle, or otherwise easy to miss.

The answer I’m looking for will be on my next post. That should be next Monday.

Want to receive an email notification when I post, or send me a comment? Drop me a line at

b l o g @ e 6 b j e t . c o m

and put ‘blog’ into the subject.

I won’t post your comments unless you explicitly tell me I can. I may edit them.

(Eventually I’ll get a feedback form working.)

Oceanic Clearance no longer needed… but you still have to ask!

“This was charming no doubt

But they shortly found out

That the Captain they trusted so well

Had only one notion for crossing the Ocean

And that was to tingle his bell.”

Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark

This change was planned for March 2024, but implementation in the Shanwick Oceanic Area has been pushed back, because, well, it’s not easy.

Watch this “North Atlantic Oceanic Entry Procedures” video, it provides good background, and is only 9 minutes. Note that it still mentions March 2024 as implementation date. Which didn’t happen for Shanwick.

Now, hot off the presses (dated September 24, 2024), out comes a video named

“Oceanic Clearance Removal – implementing ANSP’s briefing and update”. Password-protected for some reason. Try NATSOCRSept24.

It’s 1:07 long – one hour and seven minutes. But it was an interactive briefing by UK ATC, and there were pilots in the on-line audience, with questions about the process. And answers given. At times slightly (ATC-)technical, but you might still find it’s worth watching.

Both videos are from the UK Air Traffic Services provider, NATS. I found out about the second one from an email from OPSGROUP – including the password. A really great initiative by a great bunch of people! Invaluable info, especially for the corporate pilots who sometimes need the low-down on new places on short-notice. Also for dispatchers.

While researching this post, I discovered that some of my links to the ICAO NAT Office had gone stale. Here are the current ones for NAT Doc 007, the official document on NAT procedures, and for a whole lot more NAT info.

Calling this change “Oceanic Clearance Removal” wins my misnomer prize for the year.

Now, where’s my bell?

Climb / Descend via SID

This doesn’t always get the attention it deserves during training. The National Business Aircraft Association (NBAA) have done a superb job preparing an in-depth Pilot Briefing about it. Available as a PDF or as a Powerpoint document.

Go to NBAA.org Aircraft Operations – CNS – PBN and download from the Related Links sidebar on the right.

There are lots of detailed examples given for SIDs and STARs in the US. The Briefing also mentions the slight differences that apply in Canada. Invaluable for crews who aren’t in North America on a regular basis.

For the East side of the Pond, the UK CAA provides info on the topic, at SID-and-STAR-phraseology

See also Eurocontrol’s Phraseology Database, https://contentzone.eurocontrol.int/phraseology/

Shame there aren’t worked examples as in the NBAA Pilot Brief! An ounce of example is sometimes worth a pound of theory. Kudos, NBAA!

TCAS RA event with injuries

Seems a Boeing 757 enroute in the US recently responded to a resolution advisory, and 2 passengers were injured. One seriously.

Reaction to Resolution Advisories is a subject I fairly frequently address in the simulator after a check. Though I believe the sim motion cues are useful, they can’t reproduce G-forces. Sometimes a crew overreacts, but the sim doesn’t give the physical feedback that would discourage this.

So I break out Eurocontrol’s ACAS guide, which provides the following guidance.

“An acceleration of approximately ¼ g will be achieved if the change in pitch attitude corresponding to a change in vertical speed of 1 500 ft/min is accomplished in approximately 5 seconds, and of ⅓g if the change is accomplished in approximately three seconds. The change in pitch attitude required to establish a rate of climb or descent of 1 500 ft/min from level flight will be approximately 6° when the true airspeed (TAS) is 150 kt, 4° at 250 kt, and 2° at 500 kt. (These angles are derived from the formula: 1 000 divided by TAS.)”.

I point out how small the required pitch changes are.

(And sometimes that knowing good ole’ Attitude + Thrust combinations to get where you wanna be are still a useful way to fly an airplane).

TCAS phraseology is also a point that bears emphasizing in training.

I like: this blog’s metro theme

It wasn’t very hard to set up. It looks good!

Well-done, Themify. Find them at themify.me

I like: the Elgato Stream Deck +

It’s very well made. The software (I use the Mac version) is slick, intuitive, and powerful.

I’ve set it up to work with X-Plane 12 to replace a Flight Guidance Panel for my favourite aircraft, and it makes flying the sim much more of a pleasure. No more aiming with the mouse at some of those dials on screen.

Subsequently discovered it makes day-to-day life easier when working (rather than playing) on the MacBookPro. Opening folders, taking screenshots, launching programs, all that is child’s play with the StreamDeck +.

https://www.elgato.com/us/en/p/stream-deck-plus-black

Good job Elgato!

P.S. I did not receive any consideration or incentive from Elgato. It’s just a good product.

Pilot Proficiency Checks without full-motion simulator

A few days ago, Aviation International News sent out an alert, which mentions, among other things, that EASA implemented a rule change removing the mandate for a full-flight sim. The article went on to say that a particular type of helicopter VR FSTD received Level 3 qualification, and was now approved for all training and proficiency checks.

I assume that fixed-wing aircraft won’t be too far behind. It’s a sea change, and I wonder if this will improve the quality of training – for which there is always room – or just make it cheaper (pun intended).

Interesting times…